The Farmyard Offices, Mountain Honey Estate, 74 Sterkfontein avenue, Doornkloof, Pretoria, Gauteng, South Africa

The Farmyard Offices, Mountain Honey Estate, 74 Sterkfontein avenue, Doornkloof, Pretoria, Gauteng, South Africa enquiries@oneenergy.co.za

enquiries@oneenergy.co.za 0861 4328 464 or 0861 HEATING

0861 4328 464 or 0861 HEATING

Good reasons to install a photovoltaic plant on your premises

.

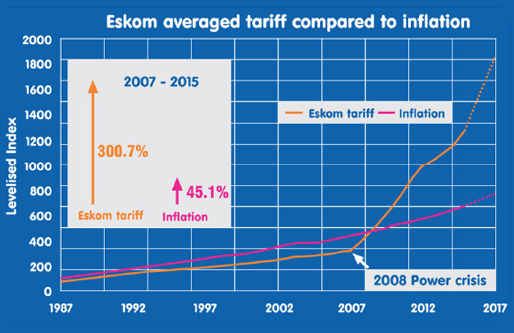

which has remained relatively static over the past 10 years. In 2007 the power supplier produced 218GWh, and it peaked in 2012 at 225GWh before dropping back to 214GWh in 2016. However, the electricity price over the same period increased astronomically from 20c per kWh in 2006 to over 80c per kWh in 2016. The impact of these increases has been significant on business and society as a whole, and an analysis of the underlying factors behind the rising tariffs is cause for great alarm.

The drop in productivity at Eskom has been staggering. Yet, over the last decade we’ve seen Eskom’s salary bill increase from R7,2bn in 2006 to over R27bn in 2016. During this period, Eskom’s staff compliment increased from 31 458 employees (2006) to over 47 978 currently. One has to ask where the extra 17 000 employees are being employed within Eskom if the company is producing less electricity than ten years ago.

When using state (and thus taxpayer) guaranteed debt, squander is terrible, but squandering borrowed – and therefore interest bearing – funds, is exponentially worse. This seems to be exactly what is happening at Eskom. The power supplier’s debt increased from just over R30bn in 2006 to over R322bn currently. More worrying is the fact that Eskom has publicly indicated this debt may increase by another R350bn in the next 5 years.

A debt of R700 billion attributed to a single state-owned entity is an astronomical amount, and poses a serious risk for the shareholders of that entity. The fact of the matter remains: the public are ultimately the shareholders who will be held hostage by repaying the debt run up by Eskom.